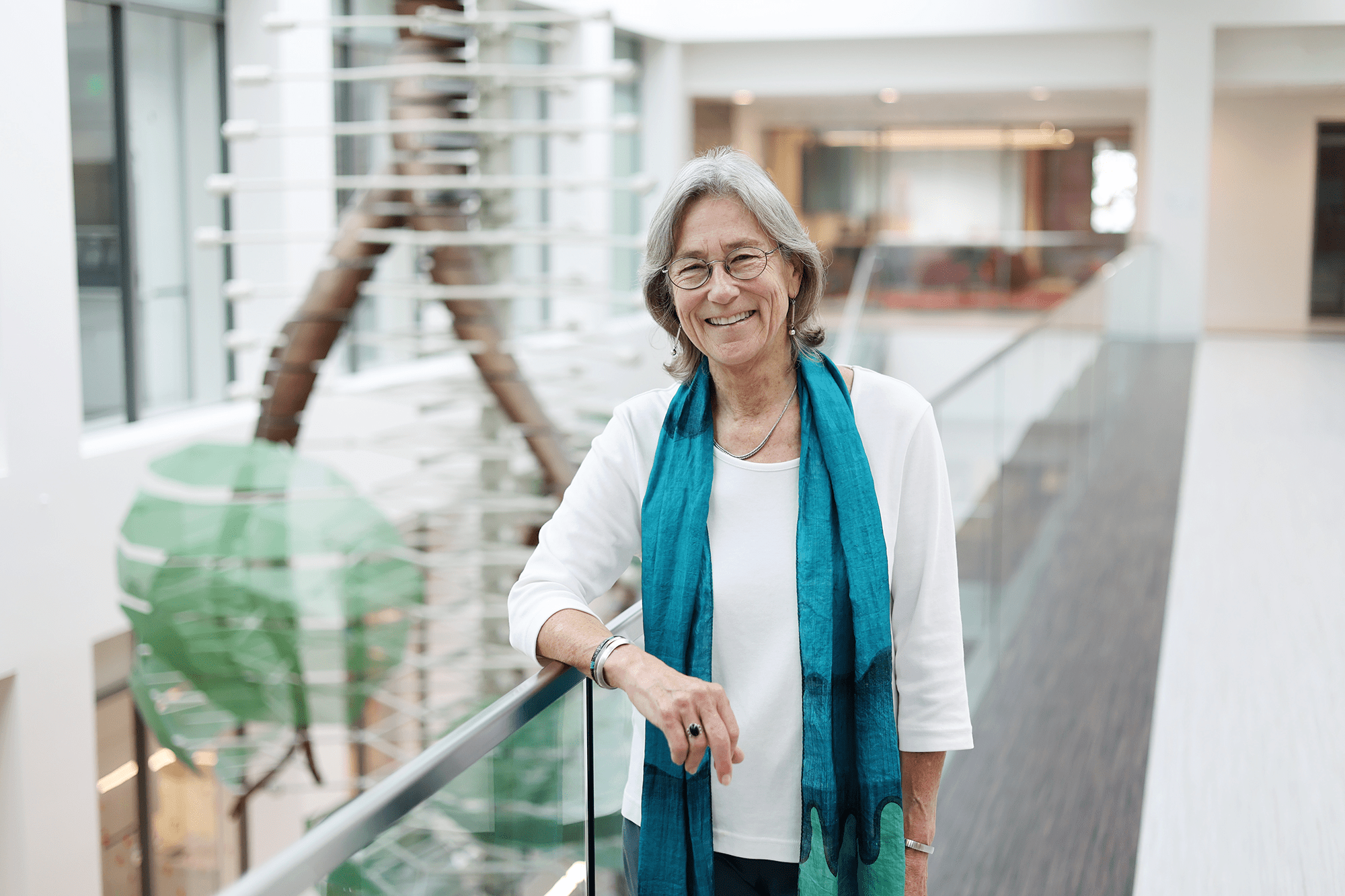

“I first stepped foot in a tropical rainforest in 1975 and have been back every year doing research on how plants defend themselves against getting eaten by insects,” says Phyllis “Lissy” Coley, distinguished professor emerita of biology at the U. She is newly elected member of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS).

NAS Members are elected to the National Academy of Sciences in recognition of their distinguished and continuing achievements in original research. Membership is a widely accepted mark of excellence in science and is considered one of the highest honors that a scientist can receive. Current NAS membership totals approximately 2,400 members and 500 international members, of which approximately 190 have received Nobel prizes. This year, Coley is the sole U faculty member to receive the honor and is the 12th College of Science faculty member to be elected.

Coley’s colleague and current Director of the School of Biological Sciences Fred Adler said of the news, “The National Academy of Sciences was established by President Abraham Lincoln to advise the nation about science and technology, and membership recognizes extraordinary achievement in research. When it comes to understanding the complexity of ecosystems and the risks they face in today’s world, Distinguished Professor Lissy Coley is the expert I turn to get to the heart of the question.”

Coley’s expertise will now be more accessible. Concluded Adler, “I am delighted that this inspirational scientist, teacher and mentor will have the opportunity to share her wisdom with our nation at large.”

A Dynamic Duo

Phyllis “Lissy” Coley and Tom Kursar

With the late Tom Kursar, Coley’s partner-in-life and in work, the couple blended her training in ecology and his in biophysics to work in multiple countries in both the African Congo and the Amazon as well as in Panama, Borneo and Malaysia.

Coley’s signature work on understanding the complexity of ecosystems is due to her focus on why tropical forests are so spectacularly diverse. “How can 650 tree species–more than in all of North America–live together in a single hectare of tropical forest?” she asks. Another question related to the first includes what drives speciation. “We have shown that the arms race with insect herbivores leads to extraordinarily rapid evolution of a battery of plant defenses,” she continues, “particularly chemical toxins, such that a given species of herbivore has evolved counter adaptations that allow it to feed on only plant species with similar defenses.”

It turns out that plant species with different defenses do not share herbivores and therefore can co-exist, promoting high local diversity. The concept that the high biodiversity of tropical forests is due to these antagonistic interactions is now widely accepted by her colleagues in the forest ecology sector and now acknowledged by the NAS.

“I am truly honored that my scientific research and conservation efforts are recognized,” said Coley, “but they would not have been possible without wonderful collaborators. And I am happy that the young scientists I have mentored are continuing to explore the many remaining questions in evolutionary ecology.”

Making it personal

To know Coley and Kursar (who died in 2018) is to know that their research is and has been highly personal. And their ambitions would naturally extend to beyond field research to economic opportunity for their friends and associates in Central America, linking even to social justice. Their concern about forest destruction and the peoples who live in those sites has led to bioprospecting. “We used our curiosity-driven (basic) research to create ways to have benefits from intact forests via drug discovery,” explains Coley. Young, expanding tropical leaves invest fifty percent of their dry weight in hundreds of chemicals. “We thought they could be an undiscovered source of pharmaceutical medicines.”

The duo set their project up in Panama, with the majority of the work being done by local scientists. It has resulted in $15 million of seed money to Panama. Their discoveries have led to promising patents, research experiences for hundreds of students and the creation of more jobs than the country’s ubiquitous and potentially destructive logging.

Left to right: Mayra Ninazunta, Dale Forrister, Yamara de Lourdes Serrano Añazco, Lissy Coley, Tom Kursar

Furthermore, the project has established the island of Coiba as a protected World Heritage Site and created a new voice of Panamanian scientists helping to shape government policy and appreciation of their natural treasures.

While Coley retired from teaching in 2020, her lab and its research, until very recently, continues at the School of Biological Sciences. “I think one of the unifying principles that made our department interesting to me,” she concludes, “is that many faculty were interested at some level in evolution.”

The late K. Gordon Lark, department chair in the 70s, was the impetus for that. “Whether we’re talking about molecular or ecological systems, evolutionary/ecological interactions shape all of that. This has been an important unifier of research interest in the School,” Coley says in tribute of Lark. Along with recent hires of outstanding young faculty researchers, which she hopes will continue, this “unifier” has helped keep such a large academic unit intact. “It has been the glue.”

As Lissy Coley always cared deeply about graduate students, she established the Coley/Kursar Endowment in 2018 to fund graduate student field research in ecology, evolution and organismal biology. The endowment is indicative of her dedication, corroborated by Peter Trapa, dean of the College of Science: “Distinguished Professor Coley has advanced our understanding of plant-animal interactions and tropical ecology in spectacular ways. Election to the National Academy is a fitting recognition of her deep and impactful contributions.”

by David Pace