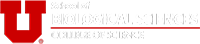

Ants are among the most numerous insects in the world, numbering from 10-100,000 trillion individuals globally with more than 10,000 species. But you don’t have to tell that to John “Jack” Longino, professor of biology.

Known affectionately as “Ant Man” in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Utah and beyond, Longino is part of a globe-spanning initiative called The Ants of the World Project that aims to generate the most complete phylogenetic tree of the ant family (Formicidae) to date.

Part of that project is Ant Course, a regularly-occurring field course on ant biology and identification. After three years of accommodating the pandemic, this year the group, involving multiple research universities, is convening in Vietnam August 1-13. During the course, the world’s ant identification experts get together to teach 24 students all about ants. Beginning in 2001, the course has been staged in the United States, Costa Rica, Venezuela, French Guiana, Peru, Uganda, Mozambique, Borneo, and Australia.

“These courses have become famous,” says Longino, “with generations of students being shaped and connected by their Ant Course experience.” The Ants of the World project, he explains, integrates teaching and research. The initiative funds three new Ant Courses in locations that are poorly known, training new generations of ant biologists while they learn about the ants of these regions.

“After a long delay due to COVID, we are finally offering our first Ant Course, in Vietnam,” says Longino of their field site in Cúc Phương National Park, just south of Hanoi. “I’m really looking forward to meeting this new group of students, interacting with Asian colleagues, and experiencing first-hand the ant fauna of Southeast Asia.” Situated in the foothills of the northern Annamite Range, the national park consists of verdant karst mountains and lush valleys with an elevation that varies from 150 meters (500 feet) to 656 m (2,152 feet) at the summit of May Bac Mountain, or Silver Cloud Mountain.

It’s all part of Ants of the World Project’s attempt to survey nearly all ant genera and just under half the described species using advanced genome reduction techniques. The result will be a comprehensive evolutionary tree of ants, out to the smallest branch tips.

The resulting data set will help researchers answer questions: Are there predictable patterns of intercontinental dispersal and diversification? Following dispersal to a new region, is there accelerated filling of morphological and climate space? How have biotas responded to climate shifts in the past? Can we predict how ants will respond to current rapid climate change?

Longino and Elaine Tan, a graduate student in the Longino lab, will be meeting up with 34 other ant specialists and ant specialists-to-be. Along with “Ant Man,” course faculty include the other principal investigators of the Ants of the World Project: Michael Branstetter (USDA-ARS), Bonnie Blaimer (Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Germany), Brian Fisher (California Academy of Sciences) and Philip Ward (UC Davis).

While Ants of the World is a collaboration of four different institutions, including the School of Biological Sciences at the U, Ant Course is organized and run by the California Academy of Science and is designed for scholars to share information and discover together the ants of a particular region. It applies ant biology to established areas of inquiry but also encourages students to ask new questions.

Zahra Saifee is a columnist at the University of Utah’s student newspaper The Utah Chronicle. She will be accompanying the team as a scientific communications specialist. She says of Ant Course, “it really is about the ants, what new species there are in [a particular region and] where species overlap. The team discusses their observations of what they’re doing with others across the world. The core is bringing diverse people to ‘nerd out’ about it for two weeks.”

A lot of the time in Vietnam, says Saifee, is set up just to explore and see what people will find. “Curiosity is at a premium, bringing observations to the group as a sounding board. People can bring to the group ‘rough drafts’ of research and ideas.”

This open-door approach to discovery was transformative for Rodolfo Probst, PhD, a member of the Longino lab who successfully defended his dissertation just this month. His 2014 Ant Course experience in Borneo connected him to a year’s work back east following his graduation from college before he settled into graduate school as part of Longino’s lab.

“Attending the 2014 Ant Course in Borneo as a Master’s Student from Brazil was a transformative experience. Not only did it imprint on me long-lasting memories of indescribable rainforest luxuriousness, but academically, that experience culminated in two significant achievements. My first peer-reviewed paper, in which I described a new ant species of a very cool-looking group of soil predators I found while attending the Ant Course, and an internship at the Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH) with Dr. Corrie Moreau (currently at Cornell University). The welcoming atmosphere at the Ant Course reinforced my desire to study ant diversity and gave me a sense of belonging in the academic universe of myrmecologists.”

~Rodolfo Probst, PhD’22

Ants are the focus of that lab’s research but it’s not just about ants. The research goals of the Longino lab involve “reciprocal illumination,” in which the latest evolutionary concepts of species formation, combined with the latest genetic tools, allow the construction of a detailed “biodiversity map” of ants. The patterns revealed in the map then inform general concepts of biological diversification.

The research has the additional benefit of allowing other researchers, like those students participating in Ant Course, to more easily identify ants. To this end, Longino helps curate a large on-line specimen and image database (https://Antweb.org), a major resource for ant researchers worldwide.

To study the way ants network can potentially speak to the design and character of larger eco-systems, Saifee suggests, making the study of ants more than a niche science. It propels one to look at the larger picture of life—not just its wonders, but its changes and adaptations. In short, its ecology and evolution. “There are a lot of different species [of ants] and how we organize data is key to new scientific discoveries,” concludes Saifee.

Making new discoveries about ants is important because, as subject models, they are on par with vertebrates and vascular plants as key taxa for ecology, evolutionary biology, biogeography, conservation biology, and public interest. Having a solid phylogenetic history opens entire new worlds of biological exploration, and has been achieved for vertebrates and many plants. With a little more effort, much of which is being addressed by the NSF-funded Ants of the World project, the same can be true for ants.

And Ant Course in Vietnam is currently at the center of that ambition.

Follow Ant Course on its blog here, also on Twitter @AntsProject You can read a student profile of graduate student Elaine Tan, who is accompanying Jack Longino to Vietnam here.