Most people get to live one life. So far, Steve Mimnaugh has lived at least three.

“I was always the new kid on the block,” he says. From Seattle to Spokane, Washington, and from Wallace, Idaho where his father worked as a mining engineer, to Kearns, Utah, to survive Mimnaugh tacked through life as an extrovert, ending up in student government. His extroversion served him well as this biology alumnus advanced into a spirited life as an emergency physician, member of a rock-and-roll band and co-founder of the innovative and celebrated ‘SPLORE (Special Populations Learning Outdoor Recreation and Education), a nonprofit founded in 1978 and dedicated to getting folks with disabilities out into white water rafting and other outdoor sports.

Diverse interests, especially as a young person, can make it difficult to get one’s footing. Such was the case for Mimnaugh, at least at the University of Utah where he moved into research during his undergraduate years, started a PhD, and haltingly applied to medical school three alternating years before being admitted to the U’s. There he was also elected class president. The deviations in his academic career seem to have had more to do with his personality rather than any kind of deficiency. In short, this self-described “granola cruncher” has been in a high evolutionary state his entire life, seemingly barreling through whole epochs in record, breathless time.

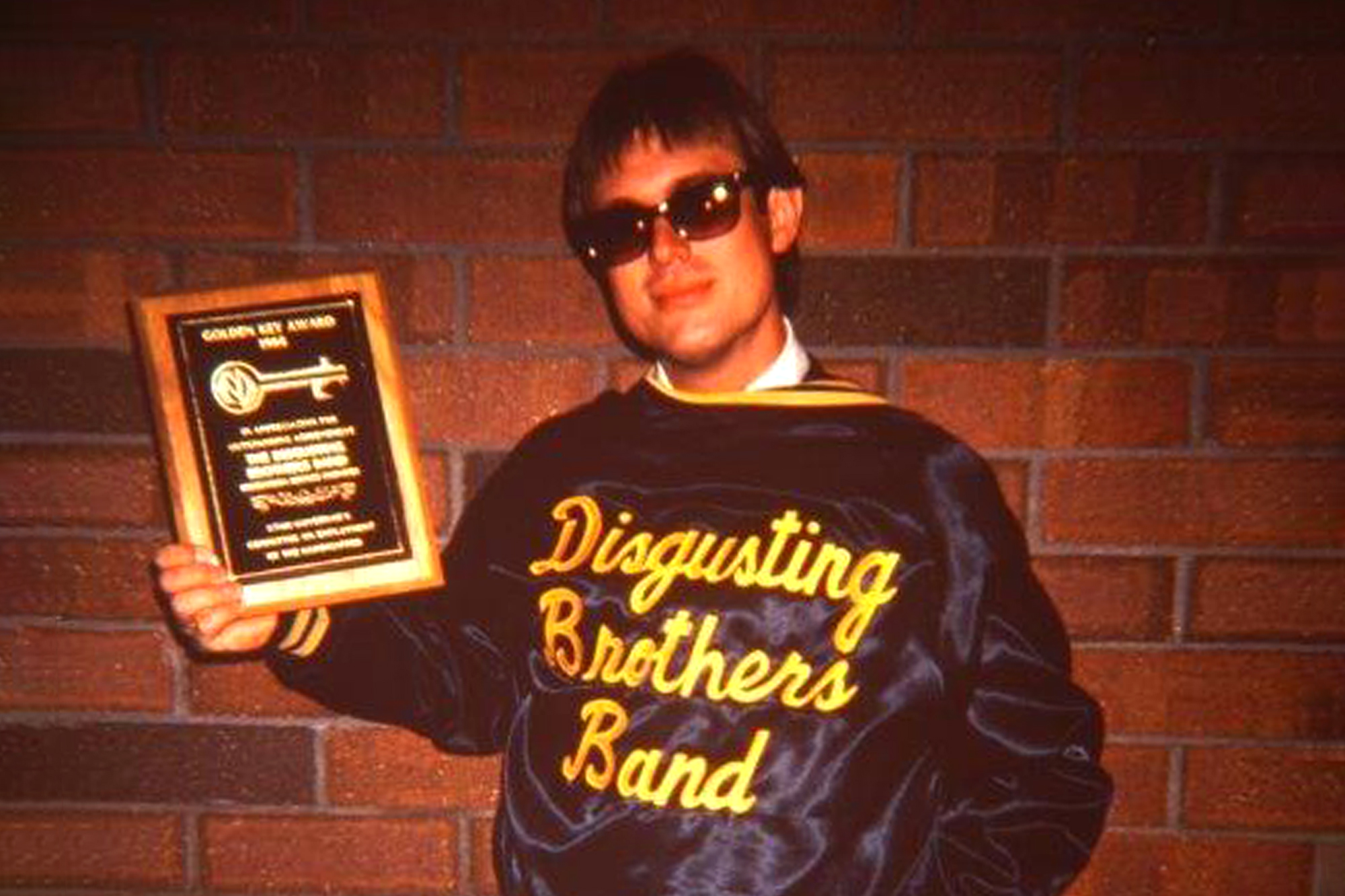

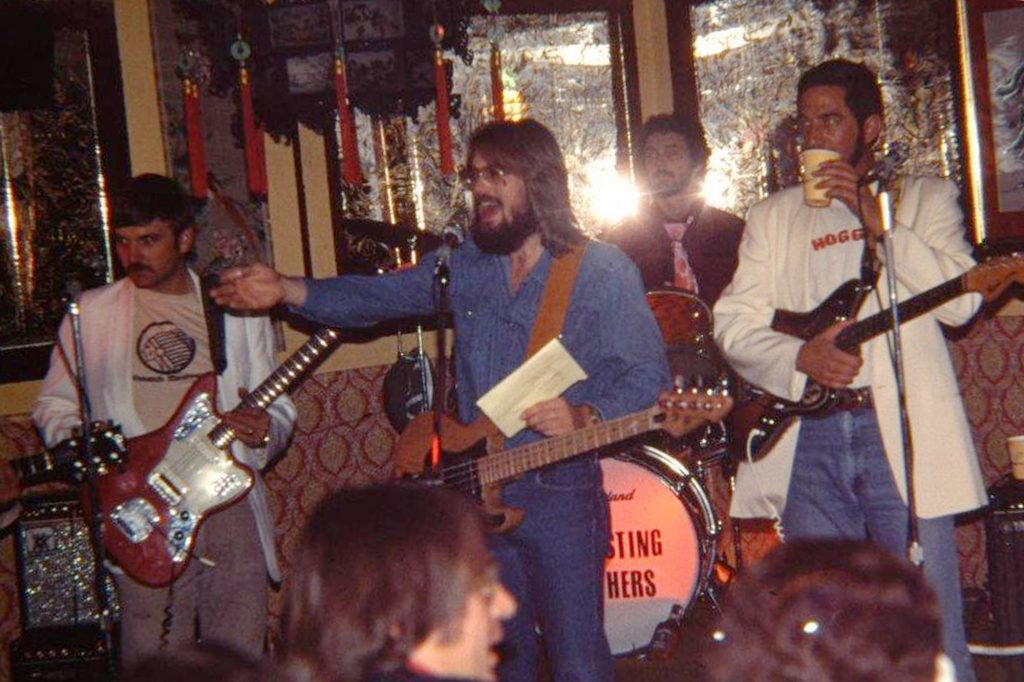

Being a biologist, evolution tracks well with Mimnaugh’s start-and-stop, somewhat circuitous path. His impetus has always been the need to adapt to a changing environment whether it be particularly onerous (sometimes bizarre) medical emergencies in critical care, securing an audience for the fledgling band The Disgusting Brothers, or raising funds to execute outdoor recreation geared toward those with disabilities. Sometimes all three lives would overlap if not converge, but his time at the School of Biological Sciences was always propulsive with associations that included future Nobel Prize laureate Mario Capecchi who was on Mimnaugh’s graduate committee and especially mammalogist and anatomist Stephen Durrant who hired Mimnaugh as a Teaching Assistant. Even so, he says, “I was not driven by [the idea of] nebulous [research] problems to work on.” Neither did he groove on all the isolation of the lab while working endlessly, it seemed, on thin-layer chromatography, mammalian cell cultures, transmembrane ion transport, and THC as an anticonvulsant. Medical school was the answer.

His experiences as an ER physician, most recently at St. Mark’s Hospital in Salt Lake City, was perfect for a restless soul who needed variety. It was also a deeply humbling experience, faced as he was regularly with society’s most vulnerable populations and some of the, potentially, most humiliating circumstances a person might find themselves in at four o’clock in the morning. “I was no one’s doctor, but everyone’s doctor,” he says. This included physician to patients with complications of acute alcohol intoxication or to someone suffering from sequestration of rectal foreign bodies. “I got a reputation,” he said, for handling emergencies that required discretion and empathy as much as medical expertise. He also developed a reputation for a bedside manner that had a way of grounding each patient having a traumatic experience back into the collective story that is both familiar and deeply human.

While coy about comparing ER work with what soldiers go through in war, he admits to suffering from a kind of PTSD that he’s had to deal with after 35 years. “I never go to sleep without having bad dreams,” he says. Writing about his experiences, now that he’s retired, has helped, and based on a cursory reading of excerpts from his nonfiction manuscript subtitled “Behind the ER Curtain,” the arc and tone of his recounting is both hilarious and touching, deeply informed by science, especially the way evolution plays out in culture and our everyday perceptions of ourselves and of each other. It’s a narrative that promises to do for the reader what Dr. Mimnaugh has regularly done for a broad spectrum of “everyman” patient: it’s okay; we’re all in this together.

It is no surprise that Mimnaugh has a counterweight—more than one, actually—to the intensity of his professional career wearing a stethoscope. As an avid river-runner in the 1970s, he was approached by recreational therapist Martha Ham who explained that there was to date no codified way of getting people with disabilities like cerebral palsy, or spinal cord-injured clients who can’t walk, swim, thermoregulate, or apply their own sunscreen safely down a river so that they could enjoy one of the greatest assets of living in Utah: the out-of-doors. Together they founded ‘SPLORE, which, he says, would not have been possible but for the work and love of thousands of volunteers who seemed to benefit as much from what was often a peak experience for them as ‘SPLORE’s clients. Both Mimnaugh’s life as a musician in an irreverent but beloved Disgusting Brothers Band and his charitable work are symbiotic. The Band whose sound has the passion of an acoustic campfire concert on a whitewater river trip—electrified and amplified–regularly plays its 60/70s favorites for fundraisers, benefiting organizations like Utah’s Hogle Zoo, the AIDS Foundation as well as, back in the day, ‘SPLORE.

Retirement for Mimnaugh seems to be wearing well for him. He recently married his long-time partner, Jay Johnson, an oncology certified nurse at Huntsman Cancer Institute. And his reading list these days ranges from Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments to the poetry of Mary Karr; and from Rituals for Finding Meaning by Sasha Sagan, daughter of the late science celeb Carl Sagan, to the cultural critique of Dave Rubin’s controversial Don’t Burn This Book: Thinking for Yourself in an Age of Unreason. Then there’s Jared Diamond’s trans-disciplinary non-fiction Guns, Germs & Steel followed by his Collapse and Upheaval. “The universe is 13.8 billion years old,” this Disgusting Brother on the bass and rhythm guitar (as well as vocals) muses, referencing Diamond: “We’re here, and in a blink of the eye we’re gone.”

But this much is certain, he concludes. “We’re good at celebrating stuff.” Perhaps that’s the embedded engine in Steve Mimnaugh for living multiple lives. You need more than one life to celebrate all of it.